MILAN — Three years ago, the greatest speedskater in American history made a rare appearance at the Olympic Oval in Salt Lake City.

Eric Heiden was curious to see the 18-year-old phenom who had already laid waste to the world junior record book and was by then beginning to snap at the heels of the fastest speedskaters on the international circuit.

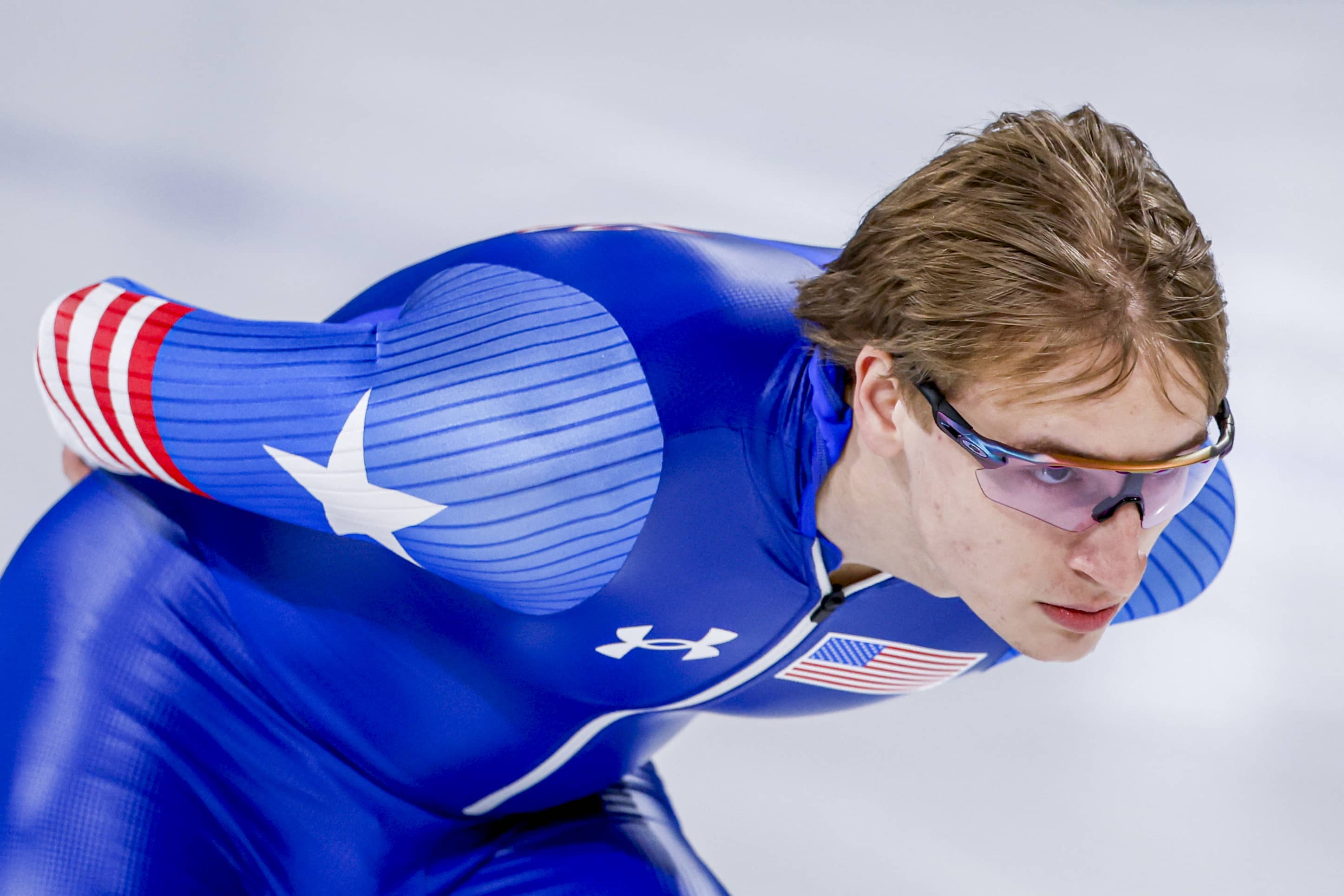

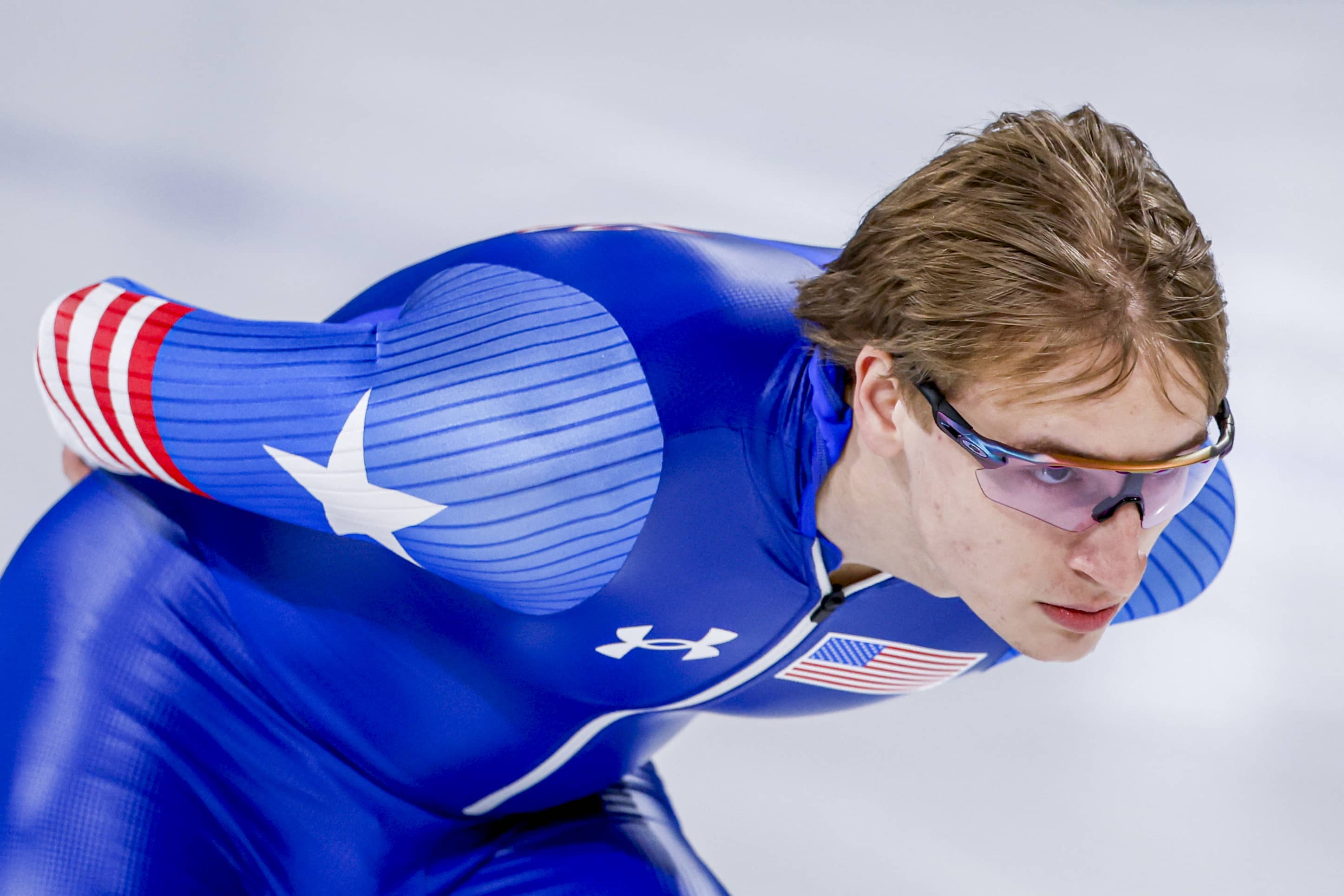

To Heiden, watching Jordan Stolz was like witnessing a younger, blonder version of himself. It wasn't just the teenager's power and efficiency in the straightaways, his ability to maintain speed in the curves or his unflappable demeanor under pressure. Their life stories also unfolded astonishingly similarly.

They both grew up in idyllic small towns in Wisconsin. They both learned to skate on frozen ponds. They both debuted on the Olympic stage at age 17 but were too young and green to contend for medals. They both came back stronger and more determined and ascended to the top of their sport during the following Olympic cycle.

"It's a little freaky how similar our histories are," Heiden, now a 67-year-old orthopedic surgeon in Park City, Utah, told Yahoo Sports. "Every time I think about it, I'm like dang, man, this guy is the same as I was."

For Stolz to live up to the label of the next Heiden, he'll need to seize his moment in the Olympic spotlight the same way Heiden did 46 years ago.

Heiden won a mind-blowing five gold medals in Lake Placid, showcasing unparalleled range by sweeping every men's speedskating race from the explosive 500 meters to the draining 25-lap 10,000 meters. To this day, no other Winter Olympian has claimed that many gold medals in a single Games. Only three other athletes have even won four gold medals at the same Winter Olympics.

Stolz, now 21, did not attempt to qualify for the long-distance races in Milan, but he's a legitimate threat to return home with gold medals in the men's 500, 1,000 and 1,500 as well as the chaotic and unpredictable mass start event. He has dominated the World Cup circuit this year, winning 16 out of 24 races that he has entered, with all of the non-victories coming in the 500 or the mass start. Those two events are the most volatile and feature the toughest competition.

Last week, Stolz publicly set a goal of winning four medals

"I can't say which colors they're going to be," he admitted with a smile.

Stolz's first chance to begin stacking medals comes Wednesday night in the men's 1,000.

Is Stolz the best American speedskater since Heiden? Yes, said Heiden, without the slightest hesitation.

"He's a once-in-a-generation athlete," Heiden added. "There hasn't been anybody better for decades."

The backyard pond

Over a quarter century ago, Dirk and Jane Stolz bought a plot of land about 45 miles outside of Milwaukee and had plans drawn up for a two-story house overlooking the forest and the prairie. They envisioned a place where their children could develop the same passion for the outdoors that they both had.

As kids, Jordan Stolz and his older sister Hannah were outside from dawn until after dark. They hiked. They biked. They caught bullfrogs. They fished in streams. They helped with the family's deer and elk farm. When Jordan and Hannah were old enough, their parents would take them to the Alaskan wilderness every summer to hunt moose and fish for salmon and halibut.

The Stolzes didn't permit their kids to watch much TV. Except when the 2010 Winter Olympics began. Dirk, a youth ski racer in Germany before emigrating to the U.S., declared to his family, "OK, for the next two weeks we're watching this."

The most frequently repeated portion of Jordan Stolz's origin story is that he and his sister fell in love with speedskating while watching charismatic short-track star Apolo Anton Ohno compete in Vancouver. In reality, Dirk also played a pivotal role.

While Dirk never had interest in team sports like baseball, football or basketball, he liked the idea of his kids pursuing a winter sport, especially one the whole family could do together. He also was aware of the rich history of the Milwaukee-based Pettit Center, the first indoor speed skating oval built in the U.S. and the place where decorated Olympians like Bonnie Blair, Dan Jansen and Shani Davis trained.

So when 5-year-old Jordan and 7-year-old Hannah were wowed by Ohno, Dirk seized his chance and gestured toward the three-acre-wide frozen pond in their backyard.

"You guys want to go out on the pond and skate?" he asked. "We can make a short track."

Days later, after their dad shoveled off part of the pond and bought two pairs of cheap hockey skates, Jordan and Hannah stumbled out onto the ice. They both wore life vests because Jane was deathly afraid of the ice cracking beneath their feet.

That humble start soon gave way to bigger things as Jordan and Hannah grew more and more obsessed with speedskating. Eventually, Dirk plowed an oval into the track so his kids could do laps and set up a light system so that Jordan could safely skate past dark.

Late one night, Jane shined a flashlight out in the backyard and found Jordan doing laps by himself. He was practicing his crossover technique to generate speed in the turns.

"You still out there?" Jane shouted.

"Just a little bit longer," Jordan replied.

That's when Jane began to realize how driven her son was.

Says Jane now with a laugh, "Even then, he was just different."

Becoming the next Eric Heiden

Before long, the pond became too small to contain Jordan's ambitions. Dirk and Jane began taking him and Hannah to the Pettit Center to work year-round with youth coaches.

One morning, when Jordan was about 10, he and Hannah whined for the first time ever to their mom, "Do we have to go to practice today?"

Jane responded as if the Cookie Monster had just turned down a plate of chocolate chip and oatmeal raisin.

"I was shocked," Jane recalled. "I was like, 'What?'"

Since the Stolzes had never needed to bribe or prod their kids to get them to practice before, Jane went to the Pettit Center to sit and watch. What she found was that her kids were standing around for so long that their feet were getting cold, that "there was a lot of talking, a lot of instructions and no skating."

Hoping for some advice, Jane approached a prominent Milwaukee-based coach with a big heart and a booming voice. Bob Fenn was best known for developing Shani Davis into a two-time Olympic gold medalist and two-time world all-around champion but he also worked with many other world-class speedskaters.

Fenn had previously seen Jordan and Hannah skate and had developed a rapport with them during their many trips to the Pettit Center. Rather than recommend a new youth coach to Jane, Fenn out of nowhere told her, "That's it. I'm taking your kids!"

To Jane, that was the equivalent of Bill Belichick volunteering to coach a Pop-Warner team. As she says, "He didn't train kids. He trained Olympians."

The Stolzes agreed to let Fenn coach their kids, but Dirk and Jane agonized over what the price was going to be. Jane repeatedly asked Fenn after practices, "How much do you charge?" Finally, he told them he would accept $250 per month to coach both Jordan and Hannah, pennies on the dollar compared to what Dirk and Jane expected.

"We basically paid for his gas money, but he didn't care," Jane said. "He loved them. He was like, I've got another Eric and Beth Heiden."

Intense yet compassionate, Fenn pushed Jordan hard for three years and got more out of him than even he thought was possible. Jordan began winning prestigious races, leading his parents to homeschool him so that he had more flexibility to handle the time demands of practicing five or six times per week and traveling to far-flung events.

Then on October 8, 2017, Fenn didn't show up to the rink for a scheduled practice session. Later that day, the Stolz family learned that the 73-year-old had passed away suddenly, the cause of deathreportedly a heart attack.

Fenn's death was very hard on both her children, Jane said. Hannah gradually retreated from speedskating, preferring to focus on her passion forraising exotic birds and doing taxidermy.Jordan also drifted. Shani Davis filled in for Fenn for a little while, but when he accepted an opportunity to coach junior skaters in China, Jordan was coachless again.

The Stolz family found an unlikely savior in Bob Corby, a close friend of Fenn who hadn't been part of the speedskating world for more than two decades. Corby coached the U.S. Olympic speedskating team in 1984 but eventually stepped away from the sport to pursue a career in physical therapy.

The retired coach and the young skating prospect had gotten to know each other before Fenn's death when Jordan suffered a hip flexor and needed a physical therapist. Corby helped Stolz with his hip, watched him skate and instantly recognized his potential.

While Corby provided guidance and advice from time to time after Fenn died, Jordan needed more than that. He and his mom called Stolz and all but begged him to come out of retirement.

"Well, I could help out," Corby said.

"We don't need help," Jane replied. "We need a full-time coach."

Intrigued by the chance to work with a talent like Jordan, Corby gradually took on a bigger and bigger role. He brought an old-school mentality on the ice and off, introducing more hill running, weight lifting and dry-land imitations to improve both Jordan's technique and strength.

The weight training in particular helped Jordan evolve from a talented but scrawny kid into a powerhouse. By the time speedskating began to emerge from the COVID pandemic, Jordan didn't just stand out among skaters his own age anymore. The teenager was ready to take on the fastest men in America.

Boy beats world

Shortly before he competed for the first time at the U.S. Speedskating Championships in March 2021, Jordan made a startling prediction.

"Mom, I can beat every one of these guys here," the 16-year-old matter-of-factly told his mother.

Jane was skeptical until she discovered those weren't just empty words from her son. Many of the top American speedskaters posted their heart rate data to the app Strava after completing road cycling workouts. Jordan had compared his own data to theirs after rides and realized that the numbers favored him.

Proof of that arrived in the men's 500 meters when Jordan outraced a field that included past Olympians and men nearly twice his age. Jordan's national junior record time of 34.99 seconds was a breakthrough that trumpeted his arrival on the international scene and foreshadowed the dominance that was yet to come.

"Everyone just went nuts," Jane said. "They were like, can you believe this? I was thinking to myself, 'Well, he told me could.'"

The eye-opening performances from Stolz didn't end there.

At 17, Stolz won both the men's 500 and 1,000 at the U.S. Olympic Trials, qualifying him to participate in the Winter Games in both events.

At 18, he swept the gold medals in the 500, 1,000 and 1,500 at world championships.

At 19, he did it again.

He might have repeated that feat a third time last year were it not for the one-two punch of pneumonia and strep throat. Even then, he still made the podium in his three signature events at world championships, claiming a silver medal and two bronzes.

While Jordan is already a superstar in the speedskating-obsessed Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe, he remains largely anonymous in his home country. Outside of perhaps the Pettit Center, he can go virtually anywhere without being recognized.

The chance for Jordan to change that begins Wednesday when he returns to the Olympic stage. NBC has promoted him as one of the faces of these Games. His image is splashed on all sorts of signs and billboards.

It's a monumental opportunity, not that Jordan seems fazed.

"I try not to think about it too much," he said. "Once you get to the line, it's the same thing you've been doing for years. Everything else around you is just noise."

Heiden plans to be in Milan to watch Jordan and support him. He has no doubt that the young American will handle the pressure well.

What Heiden can't help but wonder is whether Jordan has more in him. Could he someday enter all five men's speedskating races at an Olympics, from the 500 to the 10,000? Does he have the rare combination of sprinting speed, power and endurance to match what Heiden once did?

"I think he could be very competitive at all five distances," Heiden said. "I'm just not sure he could be competitive across the board at the same moment."

Heiden acknowledged that the competition is a lot stronger than it was in his day and there are way more athletes who now specialize in a single distance.

"To be good at the 5,000 and 10,000 may mean that he's going to lose some of his speed at the shorter distances," Heiden said. "It would be a lot to ask, but we do not know what Jordan's true abilities are yet. The sky's the limit with this guy."

MILAN — Three years ago, the greatest speedskater in American history made a rare appearance at the Olympic Oval in Salt Lake City. Eric ...

Yuma Kagiyama of Team Japan competes in Men's Single Skating - Short Program on day one of the Milano Cortina

Yuma Kagiyama of Team Japan competes in Men's Single Skating - Short Program on day one of the Milano Cortina